Please note the origin stories of these dishes, like most others, are relatively unclear because of how

intertwined Latin America’s cultures are. The dishes highlighted below are featured across the Caribbean,

Central, and South America in varying interpretations of shared ingredients.

If you have an

origin story you’d like to share, tag us on socials @aroapp.ai! We’d love to share them, too.

Happy

Hispanic Heritage Month!

By: Alexa Brunet • November 16, 2024

Latin American Cultures through Flavors: Discover the Rich Histories Behind the Most Iconic Dishes

As Hispanic Heritage Month kicks off, we wanted to celebrate our Latin culture by exploring the origins of Latin dishes and the communities that enjoy them today. From savory staples to beloved delicacies, the diversity of these dishes tells a story of tradition, history, and local ingenuity. Each bite carries generations of influence; these are the origin stories behind Mole, Arepas, Ropa Vieja, Mofongo, Pupusas, Tamales, Colada Morada, and Ceviche.

Mexico’s Mole: Layered with Flavor

Mole is one of the most iconic symbols of Mexican cuisine, known for its deep, complex flavors and rich

history. Made from a blend of ingredients like dried chili peppers, cocoa, and spices, mole dates back

to pre-colonial times when the Aztecs served a version of the sauce to emperors and as offerings to the

gods. Some claim it was even served to Hernán Cortés upon his arrival in Mexico.

While the

exact origins of Mole are unclear, the most famous variety is Mole Poblano , which is created by a blend

of chili peppers and bitter cocoa. Legend has it that a nun from the Santa Rosa convent in Puebla,

Mexico, created it in the 17th century to honor a visiting viceroy. It included a mix of indigenous

ingredients, such as chilies and tomatoes, along with products introduced by the Spanish, like almonds

and cinnamon. Another version claims the recipe was invented for a different viceroy later in the

century, though this version reportedly lacked cocoa.

Beyond Mole Poblano, other variations

are just as important in Mexican cuisine. Mole Negro , from Oaxaca, is a sweet and spicy version made

with chocolate, cloves, and cumin, and Mole Verde, which is made with pumpkin seeds and green chilies.

Mole Manchamantel incorporates fruits like pineapple and plantains, along with ancho chilies and

chorizo.

The labor-intensive process of making mole includes roasting and grinding each

ingredient for hours before cooking the sauce. Today, Mole stands as a symbol of Mexico’s culinary

heritage, and it has been recognized by UNESCO as part of Mexico’s Intangible Cultural Heritage since

2010. It continues to be served over meats, vegetables, and tortillas, embodying the country’s vibrant

history through unforgettable flavors.

A Venezuelan and Colombian Staple: Arepas

Arepas are a staple across several countries in Latin America, with roots stretching back to

pre-Columbian times. Indigenous peoples like the Timoto-Cuicas and Caribes relied heavily on maize

(corn) for their diet, transforming it into edible patties through a technique that has survived

centuries. These ancient “breads,” originally called “ erepa” by the Caribs, were prepared by tribes

across what we now recognize as Venezuela and Colombia, making arepas a truly shared culinary

heritage.

In Venezuela, arepas are a culinary staple, often eaten for breakfast, lunch, or

dinner. Traditionally, they were baked from granulated maize, a labor-intensive process that involved

drying and pounding the corn. However, this changed in the 1950s when Dr. Luis Caballero Mejías , a

Venezuelan engineer, invented a method that allowed for easier production of corn flour. The patent was

sold to Empresas Polar , and by 1960, the company had developed Harina P.A.N. , revolutionizing

arepa-making. This brand became the go-to maize flour in both Venezuela and Colombia, cementing arepas

as a cultural and culinary icon.

In Venezuela, arepas are stuffed with a wide range of

fillings—from cheese and black beans to avocado and chicken stew—making them versatile and adaptable to

any palate. Colombia, meanwhile, enjoys a similar tradition. In 2023, the city of Pereira declared the

arepa a cultural heritage, recognizing its role in national identity.

Every region, town, and

even family has its own version of the arepa, reflecting the rich diversity of Latin American culture.

Whether enjoyed simply with butter and cheese or filled with a hearty stew, arepas represent much more

than just a dish. They embody a shared history and vibrant culture, making them a beloved staple not

just in Latin America but worldwide.

The Legend Behind Cuba’s National Dish: Ropa Vieja

Ropa Vieja, which literally translates to "old clothes," is a beloved Cuban dish with a

fascinating history.

The name comes from a legend about a destitute old man who, in his

desperation, shredded his clothes to feed his family; his clothes turned into a flavorful stew of meat

and vegetables, symbolizing the man's devotion to his family. This story reflects the deep

connection between Cuban culture, culinary traditions, and family, where food serves as a medium for

bonding with family and building community.

Ropa Vieja is a hearty stew made from shredded

beef and slow-cooked with a blend of tomatoes, bell peppers, onions, and various spices. Although it may

sound uniquely Cuban, the style dish of Ropa Vieja actually originated in Spain over 500 years ago. The

recipe comes from the Sephardic Jews of the Iberian Peninsula, who would prepare a stew the night before

the Sabbath, as cooking was prohibited on that day. As the dish traveled to the Americas, it evolved,

with each region adapting it to local tastes. In Cuba, Ropa Vieja is typically served with rice and

beans, creating a comforting and well-loved meal. The dish is also popular in the Canary Islands, where

it's often paired with chickpeas.

Despite its humble ingredients, Ropa Vieja has become a

symbol of Cuban cuisine and culture. Its rich history and the legend behind its name add depth to its

already flavorful profile, making it a meaningful dish to enjoy during Hispanic Heritage Month and

beyond.

Mofongo: The Bold and Flavorful Puerto Rican Delight

Mofongo is celebrated as Puerto Rico's unofficial national dish, highlighted by its bold flavors and

rich cultural history. This savory delight consists of fried green plantains mashed with garlic,

chicharrón (deep-fried pork skin), and cilantro. While traditionally served with a bowl of chicken

broth, mofongo is versatile enough to be adapted into a main course or paired with various ingredients

like meat or butter.

The dish’s origins are a blend of Taíno, African, Spanish, and North

American influences. In the early 1500s, Spanish conquistadors arrived in Puerto Rico, subjugating the

Taíno people, the island’s Indigenous tribe. As Taíno communities faced hardship, the Spanish introduced

enslaved West Africans, who brought with them fufu, a doughy staple made from plantains, cassava, or

yams. Over time, the combination of Taíno and Spanish culinary traditions with African techniques led to

the creation of mofongo.

The name mofongo itself is derived from the Kikongo term

“mfwenge-mfwenge,” meaning "a great amount of anything at all," reflecting the dish’s hearty,

satisfying nature. This term is linked to the Angolan method of mashing starchy foods and adding liquid

and fat to enhance their texture—a practice that influenced the development of mofongo. Additionally,

the Taíno people had long used pilones (mortar and pestles) to mash ingredients, further shaping the

dish.

Today, mofongo is more than just a simple dish; it represents Puerto Rican cultural

heritage, often enjoyed during celebrations or paired with a cold beer or piña colada. Its rich, savory

profile and historical significance make it a must-try during Hispanic Heritage Month and beyond.

Pupusas: El Salvador's National Treasure

Pupusas are a cherished staple of Salvadoran cuisine, beloved for their comforting and hearty nature.

These round, thick corn flour tortillas are stuffed with a variety of savory fillings such as cheese,

pork, and chicken. The origins of pupusas trace back nearly 2,000 years to the indigenous Pipil people

of El Salvador, where they have remained a staple of rural life and have spread to urban areas over

time.

In the 20th century, Salvadoran migrants fleeing political and economic turmoil took

pupusas with them to neighboring Central American countries like Honduras and Guatemala, establishing

pupusa stands along the way. Today, pupusas can be found wherever Salvadoran communities have

settled.

Traditional pupusas are made from simple, local ingredients: maize, cheese, beans,

and loroco—an edible flowering plant with a flavor reminiscent of artichoke. Their preparation is

straightforward yet satisfying, making them both accessible and filling. Pupusas are often enjoyed in

bulk, providing a reliable and substantial meal.

As Salvadorans moved to new areas,

particularly to places like the Mission District in San Francisco, pupuserías—eateries specializing in

pupusas—emerged, bringing this delicious dish to a broader audience. Pupusas are not just a meal but a

piece of Salvadoran heritage, representing comfort and community. Their enduring popularity highlights

their importance in Salvadoran culture and their role in the diaspora.

Want to feature your restaurant on ARO?

Book a call with Alexa to learn how ARO can help you promote your restaurant’s events and offers

to the right audience—at the right time.

Tamales: An Ancient Mesoamerican Delicacy

Tamales are a time-honored dish that holds a special place in Latin American culture, with roots

extending deep into Mesoamerican history. Originating around 1000 BC, tamales were among the earliest

foods made from nixtamalized corn—an ancient process that treated corn kernels with an alkaline solution

to create masa (corn dough). This made the dough easier to work with and also made tamales a practical

and portable food for ancient hunters and soldiers.

Traditionally, tamales are made by

wrapping seasoned masa – often filled with meats, cheeses, or vegetables – in corn husks or banana

leaves, which are then steamed until cooked. This preparation technique dates back to the Aztecs and

Maya, although the exact origins are unclear. According to historical records, tamales played a

significant role in religious and cultural ceremonies, including festivals dedicated to gods like

Tezcatlipoca and Huehueteotl. They were also served at weddings, funerals, and other communal

celebrations.

Tamales are more than just a culinary tradition; they symbolize cultural

continuity. During the Spanish colonial period, while European influences tried to replace traditional

foods with wheat-based alternatives, tamales remained a staple, integrating new flavors from European

ingredients while honoring their indigenous roots.

Today, tamales continue to be a festive

food, particularly during holidays like Christmas and Día de los Muertos. The process of making tamales

often involves a tamalada—a communal event where families gather to prepare them together. This

tradition underscores tamales' role in fostering community and preserving cultural heritage.

Across

Latin America, tamales vary widely, from the savory zacahuil of Mexico to the sweet “pamonhas” of Brazil

and the plantain-based “pasteles en hoja” of the Dominican Republic. Each version reflects local

ingredients and cultural influences, showcasing tamales as a versatile dish deeply rooted in the

region’s history and identity.

Colada Morada: Ecuador’s Flavorful Beverage with Indigenous Roots

In Ecuador, colada morada is a traditional beverage enjoyed on November 2nd, the Day of the Dead. This

drink, alongside "Guaguas de Pan" (bread figures), has its roots in ancient Indigenous

celebrations. Originally part of the Aya Marcay Quilla, or "month of raising the dead,"

practiced by the Incas, it evolved after colonialism when Indigenous and Spanish traditions merged.

Historically,

the Incas prepared a drink called "uchucuta" for this festival. Made from black corn mixed with

medicinal herbs, potatoes, beans, peas, cabbage, and achiote, uchucuta was served with pumpkin

tortillas, honey, and beeswax. This indigenous custom adapted over time, blending with Spanish

influences to form the modern Colada Morada.

Today, Colada Morada is made from black or

purple corn, ground into flour and mixed with an infusion of herbs, blackberries, mortiño (Andean

blueberries), naranjilla, and various fruits like strawberries and pineapple. It is typically enjoyed

with Guaguas de Pan, which are bread figures shaped like little children, decorated with colorful faces

and filled with sweet treats such as guava jam, dulce de leche, or chocolate.

While the base

ingredients remain similar, the recipe for Colada Morada varies by region and family, each claiming

their version is the most authentic. This variation reflects a deep cultural tradition where each family

continues to prepare Colada Morada according to their cherished recipes passed down through generations.

Ceviche: The Fresh, Zesty Dish of the Pacific Coast

Ceviche, a quintessential dish of the Pacific coast, boasts a rich history that extends far beyond its

recent popularity in global cuisine. While it may seem like a modern creation, the roots of ceviche

trace back over 3,000 years to the coastal regions of Peru, particularly around Huanchaco. Early

fishermen are believed to have enjoyed their catch straight from the sea, although the exact methods

used in ancient times remain undocumented.

The Moche people of pre-Columbian Peru did not

have the citrus fruits now integral to ceviche. Instead, they relied on indigenous chilies and possibly

seaweed to season their fish. The arrival of citrus fruits, such as lemons and limes, only came after

the Spanish and Portuguese introduced them in the 16th century. Some historians suggest that the early

ceviche-like dishes may have used the juice of the tumbo, a passion fruit relative, until limes became

available.

Ceviche’s evolution continued as it spread along the Pacific coast. In Huanchaco,

local cevicherias use Peruvian limes and kelp (cochayuyo) to prepare this dish, reflecting regional

ingredients and traditions. However, ceviche only gained widespread popularity in Lima about 60 years

ago, thanks in part to Japanese immigrants who refined the dish by serving it immediately after

marination, preserving the freshness of the fish.

Though Peru is often celebrated as the

birthplace of ceviche, variations of this dish are enjoyed throughout Latin America. In Ecuador,

ceviches might include tomatoes and peanuts, while in Mexico, ceviche often features avocado and is

served in tacos or as a seafood cocktail. The dish's popularity extends beyond Latin America;

similar preparations can be found in the Philippines and even in European cuisines, suggesting a shared

appreciation for marinated fresh fish across cultures.

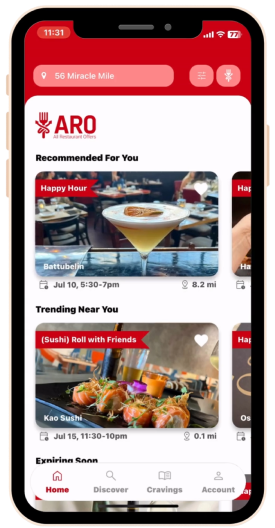

CELEBRATE HISPANIC HERITAGE

MONTH WITH ARO - ALL RESTAURANT OFFERS

Exploring the origins of these iconic Latin dishes gives us a glimpse into the rich histories

that shape Latin American cultures. Each dish tells a story of resilience, creativity, and

tradition, all of which are worth celebrating during Hispanic Heritage Month.

Ready to

embark on your own culinary journey?

Download ARO - All Restaurant Offers

to discover restaurant promotions and events near you.

Whether craving Mole, Mofongo,

or Ceviche, ARO connects you to the best Latin flavors in Miami!

Alexa is a seasoned content and copywriter with over 9 years of experience crafting targeted, well-researched content. As the voice behind ARO’s blogs and guides, she brings her passion for the restaurant industry to life—helping food lovers discover the best dining deals and experiences.

Want to feature your restaurant on ARO? Book a call with Alexa to learn how ARO can help you promote your restaurant’s events and offers to the right audience—at the right time.

Best Wine Deals in Miami by Neighborhood

Miami's dining scene is famous for its legendary blend of Latin cultures, flavors, and energy, which keeps foodies coming back for more.

11 Fancy Valentine’s Day Dinners in Miami

Trust us when we say, ditch the box of chocolates and take your special someone for a romantic dinner instead this Valentine’s Day — but flowers are still non-negotiable.

Best Miami Restaurant

Offers for this January-2025

’New Year, New Me’ wouldn’t be complete without New Dining Experiences, so here are 10 reasons you

should add them to your 2025 resolutions and more.

ARO - All Restaurant Offers is the only app that

personalizes restaurant offers to each individual’s taste. Currently headquartered in Miami, FL, we

wanted to share some of our must-tries for January 2025.

What better way to start the new year than

by treating yourself and satisfying your cravings?